By: Deden Mauli Darajat

In today’s rapidly advancing era of globalization, the concept of a “global village,” popularized by Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s, has become ever more relevant, considering how technology, culture, and history serve as bridges connecting cities in different parts of the world. One intriguing example of this connection is the presence of the name Multatuli, which has become a symbolic link between two geographically and culturally distant cities—Rangkasbitung in Indonesia and Amsterdam in the Netherlands. This name is not merely an ordinary label; it is laden with historical and philosophical meaning. In this context, the concept of a global village is not only about modern integration but also about the acknowledgment and respect for a shared historical narrative.

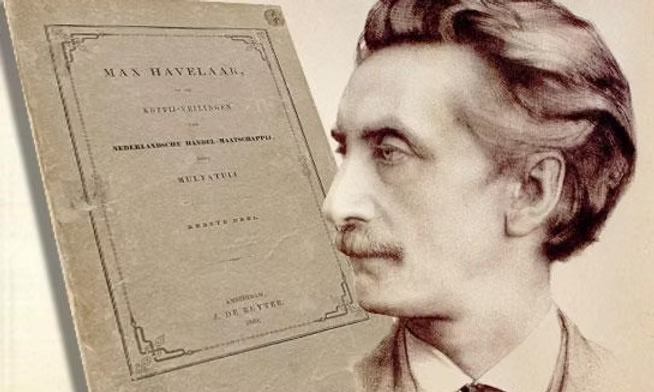

Multatuli was the pen name of Eduard Douwes Dekker, a Dutch colonial official who served briefly as Assistant Resident of Lebak (including Rangkasbitung) in 1856. During his short tenure, he directly witnessed the injustices of the forced cultivation system (cultuurstelsel) imposed by the Dutch colonial administration in the region. This bitter experience inspired Dekker to write his novel Max Havelaar under the pen name Multatuli—Latin for “I have suffered much.” The novel became a landmark work that opened the world’s eyes to the suffering of indigenous people under colonialism in the Dutch East Indies.

In Rangkasbitung, Multatuli’s name was immortalized through the establishment of the Multatuli Museum, housed in a historic building that once served as the Kawedanaan Lebak office. Originally built in 1923 in the Indies architectural style, the museum is more than a repository of artifacts—it is a reminder that the history of colonialism and the struggle for social justice should not be forgotten and should instead serve as lessons for present and future generations. The museum embodies a historically grounded sense of the global village, for although it stands in Indonesia, it is tied to an internationally recognized name—Multatuli—linking it culturally to the Netherlands, the author’s homeland.

In Amsterdam, there is also a Multatuli Museum dedicated to showcasing the history and works of Eduard Douwes Dekker, including replicas and key documents related to Max Havelaar. The existence of two museums bearing the same name in different parts of the world illustrates a form of historical global village: a cross-border, cross-cultural relationship embodied in collective spaces that remember and advocate for justice and humanity. Although the Rangkasbitung and Amsterdam museums have no formal institutional ties, they are united by the figure of Multatuli and his spirit of resistance against colonial oppression. In fact, some collections from the Dutch museum have been sent as donations to Rangkasbitung.

This phenomenon illustrates that the global village is not solely about ease of communication, travel, or trade but also about sharing and preserving collective memory, strengthening identity and solidarity across borders, and rooting them in a shared history. Rangkasbitung and Amsterdam, though far apart, are “connected” by the name Multatuli—a name that carries moral and critical messages against oppression, transcending time and space.

On one hand, this offers an important lesson that a genuine global village must be built on understanding and respecting history and justice. Renaming public spaces such as museums, streets, or institutions after Multatuli in Rangkasbitung is not only about commemorating the past but also affirming the importance of openness and critical dialogue about colonialism and its impacts. It helps local communities and visitors understand that their city is part of a larger historical narrative that also involves nations across the globe.

Moreover, this linkage through the name Multatuli can strengthen bilateral relations through cultural and educational channels. The museum in Rangkasbitung has become an educational hub for students and the public to learn about colonial history and the struggle against injustice, inspired by the moral courage of a colonial official who dared to speak the truth. This creates a cross-cultural dialogue that highlights how globalization does not necessarily mean cultural homogenization but can also foster recognition of diversity and critical dialogue. The museum thus stands not only as a local heritage site but as a part of global human heritage.

This perspective shows how names and history can serve as powerful tools to build bridges between geographically distant regions, yet connected through history and shared human values. Multatuli has become a symbolic connector, weaving together moral and historical narratives between two cities in different hemispheres. This represents a global village concept that goes beyond physical and technological integration—embracing the deeper integration of cultural and historical legacies as social capital linking communities across nations.

In conclusion, the connection between Rangkasbitung and the Netherlands through the name Multatuli demonstrates how a global village can be realized through honoring shared history and universal human values. The Multatuli Museum in Rangkasbitung, together with its historical relationship to Amsterdam, is concrete proof that intercity connections are not always about physical infrastructure or advanced technology—they can also be woven through layers of meaning and collective narratives that transcend national borders. The critical and humanistic spirit embodied by Multatuli serves as a bridge of understanding and solidarity between two cities separated by distance but united in a single story and a single name, affirming that the world is indeed one interconnected village—linked not only economically and politically but also culturally and historically.